Five years ago—on December 4, 2019—I got my cancer diagnosis. I still remember it clearly. Two days earlier, I’d had a suspicious mass in my left breast biopsied. Honestly, I wasn’t thinking much about it because I’d had a similar biopsy two years earlier in my right breast and it was benign (fibroadenoma).

That was Monday. Wednesday evening, my husband had just left to head to trivia night with friends. I wasn’t feeling great, which is pretty normal for me, and decided not to go with him. Shortly after he left, I realized I had a missed call from earlier in the afternoon, so I pulled up the voicemail from a number I didn’t know.

The message was 44 seconds. It’s still on my phone. In the voicemail, the doctor who’d performed my biopsy said she wanted to call because my biopsy results came back early and the office was closing, so she asked me to call her back on her cell phone. At that point, I knew something was wrong, as typically benign reports get uploaded into patient portal and maybe you get a call to let you know. If it was benign, why would she have wanted me to call her back immediately? So I called her back and she confirmed my suspicion—the biopsy was positive for invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). She noted how surprised she was given my age and having no family history. She let me know that the process would be fast and the office would contact me the next day about scheduling appointments to come up with a treatment plan. I called my husband, asked him to come home, and told him the news. Only then did I cry.

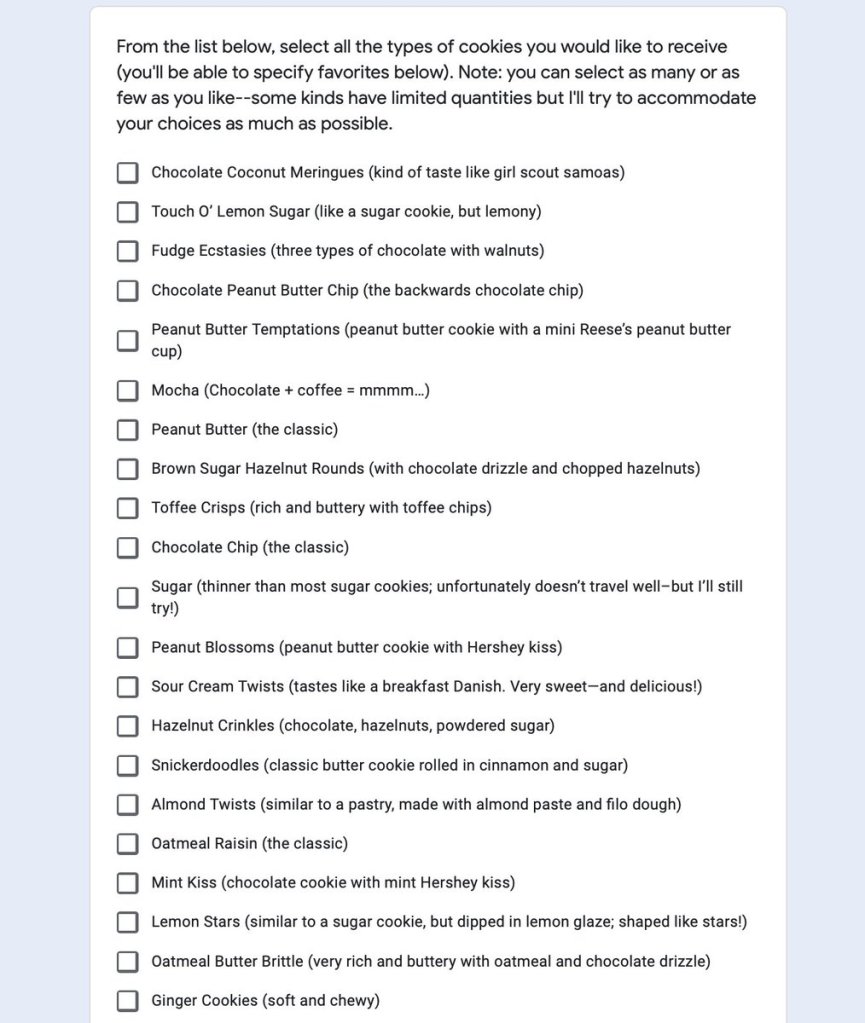

The next month was a whirlwind of appointments, scans, and bloodwork in between work, cookie baking, and holiday festivities. My genetic testing was negative for the common mutations (BRCA), which was great news. I then had a lumpectomy in early January 2020, where they removed two tumors and five lymph nodes, one of which was positive for cancer, making my cancer Stage 2A. A sliver of my tumor was then sent off for additional tests to determine if I would benefit from chemo.

If I’m being honest, this is when I was most terrified—I’m not a vain person but losing all my hair and having a very visible reminder of the cancer kept me up at night. Ten years earlier, I would have had chemo by default because of the lymph node involvement but cancer testing—and especially breast cancer testing—has greatly improved. After my specimen was “temporarily lost” for several weeks, I finally got the great news that chemo would not be beneficial. Instead, I just need six weeks (30 sessions) of radiation.

After some consultations and a “radiation simulation” session, I began my six weeks of daily radiation sessions on March 11, 2020. This happened to be the same day the WHO declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic. The second day of radiation, we were told we’d need to have masks on at all times. The third day of radiation, they began to separate the radiation patients from other oncology patients.

I turned 40 during my radiation sessions. That was pretty bittersweet. Then two weeks later, I got to ring the bell after my 30th session. I had finished active treatment, and now shifted to regular checkups with my doctors, 5-10 years of an estrogen blocker (tamoxifen), and scans every six months. Earlier this year, I was able to take a test to confirm I didn’t need more than five years of tamoxifen, meaning I can stop next March. This was very good news indeed, as tamoxifen has some gnarly side effects.

Obviously, I still think about my cancer frequently, and I know it could come back at any time. The challenge I think many people have is not letting that fear rule their lives. Here are some things that may have helped me.

I had already been chronically ill for 14 years when I got my cancer diagnosis.

I was a sick kid and a sicker adult. After several years of increasing GI issues in my early 20s, I was diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease when I was 25. Since then, I’ve developed chronic migraines and asthma. I had a bad case of Lyme that took a year to resolve. I have had daily chronic fatigue for well over a decade.

All of this is to say that while the cancer diagnosis was certainly scary, at some level it felt like I had been preparing for this for a long time. Taking daily meds was a part of my life. Regular scans were uncomfortable but not intimidating—I’d had multiple encounters with MRI machines before my first breast MRI.

Breast cancer research is tremendously well-funded.

Thanks in part to former president Bill Clinton, whose mother died of breast cancer, breast cancer treatment is enshrined in law—in 2000, Clinton signed the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act to cover prevention and treatment of cancer. It is also the most funded cancer in terms of research dollars (think billions of dollars), and treatment has evolved quickly. I benefited from these advances in numerous ways—the Oncotype test did not exist 10 years earlier, and it is only because of that test that I didn’t have to go through chemo. My cancer was on my left side, which is problematic because my heart is also there, but radiation treatment has gotten tremendously precise in recent years and I was able to go 30 rounds without fear of heart damage.

Breast cancer is always scary, but I do believe my treatment was much less invasive thanks to all these advances.

My cancer case was very straight forward… or at least as straight forward as cancer can be.

When you get diagnosed with breast cancer, you are also told if it is hormone positive for three types of hormones: estrogen, progesterone, and HER2. I had the most common type of cancer: invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC++-), meaning I was estrogen and progesterone positive and HER2 negative. In other words, my cancer feeds off of estrogen and progesterone, which is why I’ve been on tamoxifen the last five years.

IDC++- has a very straightforward treatment, and when I had my lumpectomy, I got “clear margins” on the first go, meaning when they took out the tumor, they took out a layer of tissue around the tumor and tested it, finding no cancer cells in the outside layer. Yes, my radiation treatment was complicated by the pandemic, but I had no real issues and minimal side effects from it. The tamoxifen is a different story, but even then it has been manageable.

My work situation was pretty ideal for cancer treatment.

If I were to find a silver lining to having cancer treatment during the early days of a pandemic, it’s that I was on sabbatical at the time, which meant I was not having to deal with the many challenges my colleagues were related to shifting classes online, figuring out how to balance work and their small children, and so on. I just had to drive to the hospital each day for an hour to be blasted with radiation. The downside is that I didn’t get a real sabbatical, but I can’t imagine having to deal with diagnosis and surgery and treatment while having all my normal work responsibilities.

I’m a scientist and can (more easily) read and interpret scientific papers.

No, I’m not “that kind of doctor,” but being a PhD and being familiar with research made it easier for me to dig into the literature on my type of cancer and treatment options. I think this helped ease some anxiety.

I also highly recommend the book “Radical: The Science, Culture, and History of Breast Cancer in America” by Kate Pickert. I listened to this shortly after my diagnosis and it was very reassuring.

Being open about my diagnosis helped a lot.

After my surgery, I started emailing a group of friends and family regular updates about what was going on. In these emails, I tried to demystify cancer treatment and walk them through all the various factors being considered. I found the process of writing all this out and focusing more on the science/clinical aspect of cancer really helped me to move beyond purely emotional reactions.

In the years since, I have been pretty open about my dx on social media and that has been incredibly rewarding. We don’t talk enough about chronic health conditions, but many people are affected by them. Many women have reached out to me to share cancer scares or to let me know that my experience led them to get their first mammogram. That makes everything worth it.

I recently had my biannual appointment with my oncologist, and remember telling him that it feels weird that my cancer is the least of my concerns health-wise. While it was an acute health crisis for about six months of my life, I feel lucky that I have only had a few complications in the years since. My other health issues, unfortunately, remain my constant companion and continue to take a toll. The cancer is always lurking in the background, but there’s little I can do to prevent it from reoccurring outside of what I’m doing—taking my meds and getting regular scans.

Five years ago, I was left in a state of shock, but I also knew I had tremendous resolve and a solid support network to get me through this. My colleagues and collaborators took great care of me, giving me a year of Audible credits and officially getting me hooked on audio books. My husband was my rock and took great care of me.

With their help, I made it through to the other end with just two scars to remind me of that time of my life and even more resilience to respond to the things life throws at me. I hope you never have to go through what I did, but if you do, I hope your cancer journey is even easier than mine. Know that I will be rooting for you to kick cancer’s ass.

BOOK REVIEW OF: boyd, d. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 271 pages.

BOOK REVIEW OF: boyd, d. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 271 pages.